Fuzzers, Blind Spots, and the Importance of Context in Vulnerability Research

- Nov 11, 2025

.png)

We’ll share how we discovered vulnerabilities through static analysis, analyzed the underlying code, and explored why certain types of fuzzing failed to catch what appeared to be a textbook buffer overflow (BOF). We’ll also discuss how complementary approaches like instrumentation and threat modeling can help catch bugs that fall through the cracks of fuzzers.

A Quick Word About the Project: crun

Our research was conducted on crun , a fast and lightweight OCI (Open Container Initiative) runtime written in C. It’s designed as a drop-in replacement for runc and is often used in container ecosystems like Podman. Given its close interaction with system-level components and user-supplied inputs (like configuration files and runtime parameters), crun is a critical component in modern container stacks making it an attractive target for vulnerability research. The project includes a mix of hand-written C logic, seccomp filters, and integrations with lower-level kernel APIs. This setup makes it an ideal candidate for both static and dynamic security analysis.

Spotting a Classic BOF

During a manual code audit, we found a suspicious use of strcpy , which is always a red flag in C due to its complete lack of bounds checking. We immediately checked whether attacker-controlled input could reach this strcpy call without validation. Here's the relevant snippet:

int main (int argc, char **argv)

{

...

socket = open_unix_domain_socket(argv[1]);

...

return 0;

}

open_unix_domain_socket (const char *path)

{

...

strcpy(addr.sun_path, path);

...

}As you can see, argv[1] is passed directly to strcpy , making it trivially exploitable at least in theory.

Can Fuzzers Catch It?

Interestingly, in the same directory, we found a hongfuzz.sh script. Curious to see if the included fuzzer would detect this issue, we ran a few quick experiments.

First, we validated that honggfuzz was working with this simple vulnerable code:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

char buff[256];

puts("HI");

gets(buff);

return 0;

}

We fuzzed it using:

honggfuzz -i input_dir/ -x -s -- ./run

After about 27 seconds, it crashed:

Crash: saved as '/crun/contrib/seccomp-receiver/SIGABRT.PC.7ffff7e1f9fc...'

We then tried a slightly more realistic example using strcpy:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char buff[256];

puts("HI");

strcpy(buff, argv[1]);

return 0;

}Again, honggfuzz quickly found crashes:

Crashes : 123 [unique: 1, blocklist: 0, verified: 0]

So far, so good.

Real Target, Real Surprise: No Crashes

Encouraged, we ran the fuzzer on the actual binary that contained the strcpy vulnerability. We let it run for 24 hours. Result?

Crashes : 0 [unique: 0, blocklist: 0, verified: 0]Perplexed, we manually executed the program with an oversized input. It didn’t crash.

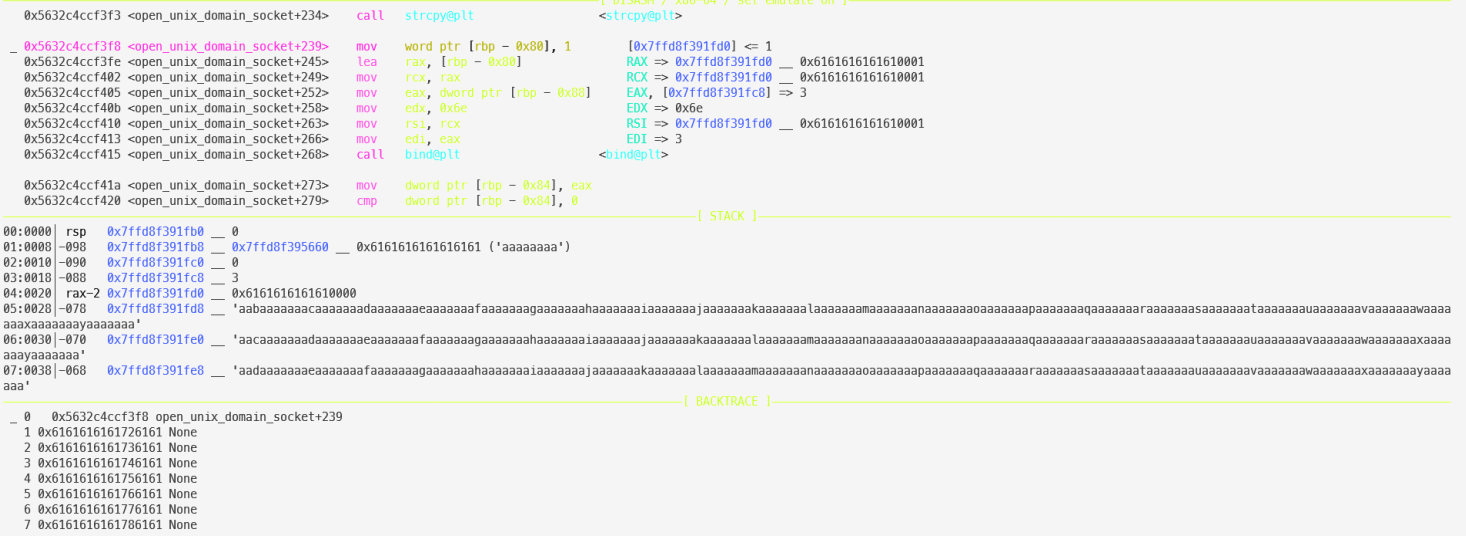

We set a breakpoint at open_unix_domain_socket+234 to inspect the stack:

After allowing strcpy to execute:

The stack was clearly corrupted. However, the program didn’t crash.

Why the Program Didn’t Crash

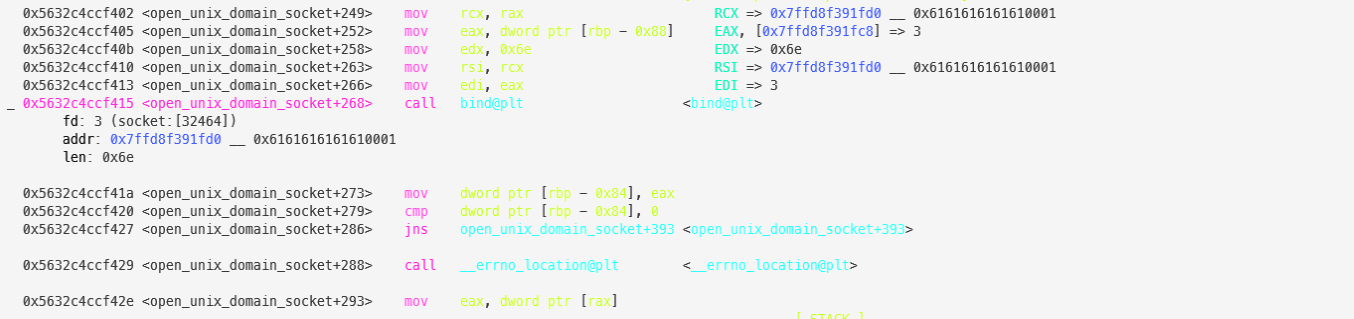

We dug deeper and set breakpoints around the bind call. Here's what we found:

Before bind :

After bind :

The bind call fails because it attempts to bind to the overflowing sun_path , which doesn’t correspond to a valid socket or filesystem path. The error path triggers an early return before corrupted stack data is ever used.

This explains why fuzzing missed it. The fuzzer couldn’t simulate a valid file path to reach deeper execution paths. Even though strcpy is unsafe, the crash path remained unreachable due to environmental dependencies like filesystem state.

The Role of Instrumentation: ASAN to the Rescue

Could the bug have been caught with instrumentation? Yes.

Compiling the binary with AddressSanitizer (ASAN) would have immediately detected the buffer overflow even if the program exited early due to a failed bind.

This case highlights a key lesson: no single technique is sufficient. Static analysis found the bug quickly. Fuzzing failed due to environmental limitations. Instrumented fuzzing (e.g., with ASAN) would have succeeded.

A Second BOF: The chroot_realpath Case

During our broader analysis, we uncovered another buffer overflow, this time in the chroot_realpath function. Here's the vulnerable code:

sprintf (resolved_path, "%s%s%s", got_path, path[0] == '/' || path[0] == '\0' ? "" : "/", path);

The function writes into resolved_path without checking the length of the inputs. This is classic unsafe behavior.

Creating a PoC

To trigger this, we wrote a small PoC using libcrun :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <limits.h>

extern char * chroot_realpath(const char * chroot, const char * path, char resolved_path[]);

Build Instructions

We then ran the binary under gdb , placing a breakpoint at chroot_realpath.c:138 .

Once the vulnerable line was executed, we observed the stack was smashed:

int main(int argc, char * argv[]) {

if (argc != 3) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s \n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

const char * chroot_str = argv[1];

const char * path_str = argv[2];

char buffer[10]; // Intentionally small buffer to trigger overflow

char *result = chroot_realpath(chroot_str, path_str, buffer);

return 0;

}Build Instructions

apt update -y

apt install libsystemd-dev libseccomp-dev libcap-dev libyajl-dev autoconf automake libtool -y

git clone https://github.com/containers/crun.git

cd crun

./autogen.sh

./configure

make gcc -o poc poc.c -I./src -L./.libs -lcrun

./poc "A" "BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB"

We then ran the binary under gdb , placing a breakpoint at chroot_realpath.c:138 .

Once the vulnerable line was executed, we observed the stack was smashed:

Understanding the Root Cause

The core issue is that resolved_path is a caller-supplied buffer:

char *chroot_realpath(const char *chroot, const char *path, char resolved_path[])

Because it's passed by pointer, we can't use sizeof to get its size. Using strlen isn't reliable either zeroed or uninitialized buffers could produce false readings.

The ideal fix is to modify the function to accept the buffer's size:

char *chroot_realpath(const char *chroot, const char *path, char resolved_path[], size_t buffer_len);But this would require refactoring every place where the function is called.

Is the Fix Worth It?

We examined how chroot_realpath is used in crun . It turns out it’s only used internally, and all its current calls use buffers sized with MAX_LEN , which safely prevents overflow.

So, while the function is technically vulnerable, it is not practically exploitable in its current use. This raises an important takeaway: context matters. Sometimes, a function may be vulnerable in isolation, but safe in its current deployment due to how it’s called and used.

Lessons Learned

This case teaches us that technical vulnerabilities can exist without being practically exploitable. The broader context in which code is used plays a crucial role security is not determined solely by the presence of a bug, but also by how and where the affected code is integrated. This highlights the importance of comprehensive threat modeling when evaluating the real risk and impact of a vulnerability. Understanding the surrounding environment, privilege boundaries, input sources, and deployment conditions is essential to accurately assess exploitability. In other words, identifying a flaw is only the first step; determining whether it poses a real-world threat requires examining the entire system context.