We’ll be diving deep into the recent CrowdStrike outage that sent shockwaves across the global IT landscape. Our aim is to shed light on the events that unfolded, exploring what went wrong, why it happened and most importantly, how organizations can safeguard themselves against similar disruptions in the future.

Understanding the root cause of such an outage is critical for IT professionals and cybersecurity experts alike, as it offers valuable lessons that can help prevent potential threats and ensure business continuity. So, let’s dissect the CrowdStrike saga and uncover the key takeaways to keep your organization secure and functioning.

CrowdStrike is a globally recognized leader in cybersecurity, renowned for its expertise in defending against malware and ransomware attacks. Their cutting-edge tools empower organizations to protect themselves from both known and emerging threats, making CrowdStrike a trusted name in the industry.

At the heart of their offerings is the Falcon Endpoint Detection & Response (EDR) software—a flagship product that plays a pivotal role in safeguarding businesses against malicious attacks. However, in the recent global IT outage, Falcon found itself at the center of controversy, as a critical update led to widespread disruptions.

As cyber threats have evolved, traditional antivirus software has proven insufficient in defending against modern attacks. To counter this, the cybersecurity industry developed Endpoint Detection & Response (EDR) solutions, which collect extensive data from users’ systems (endpoints) and provide a centralized interface for security professionals to analyze this data and respond to threats in real time.

CrowdStrike’s Falcon is a leading EDR solution. It gathers comprehensive telemetry data from endpoints, including network traffic, process activity, file system events, and operating system activities. This data is then made accessible through a web-based interface, allowing cybersecurity teams to quickly identify and remediate potential threats.

At the heart of Falcon's functionality is the Falcon Sensor, a lightweight software agent installed on endpoints. This sensor continuously collects telemetry data and transmits it in real time to CrowdStrike’s servers, enabling swift analysis and response to any detected anomalies or attacks.

To effectively protect endpoints, Falcon Sensor requires access to critical system events. However, this level of access isn’t always granted by the Windows operating system to third-party security vendors. To overcome this challenge, CrowdStrike, like many cybersecurity companies, employs a dual-layer approach to data collection.

Falcon Sensor operates through two sets of information-gathering services: one at the user level and the other at the kernel level. The user-level service functions like any other software on the system, while the kernel-level service operates as a device driver, similar to how the Windows operating system itself runs. This dual approach allows Falcon Sensor to capture a comprehensive range of data, providing visibility into all levels of the operating system.

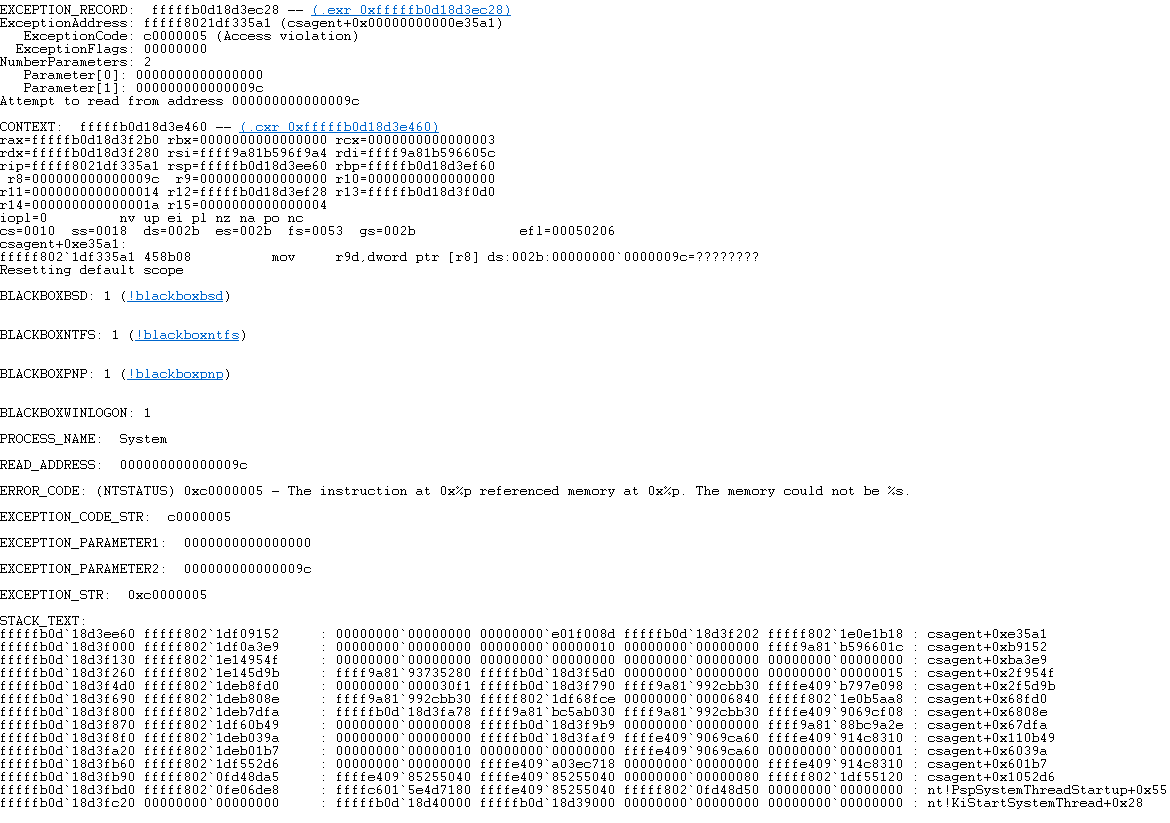

The user-level service is a straightforward executable, but the kernel-level service is more complex, functioning as a device driver named csagent.sys. Unfortunately, it was an error in this device driver that triggered the recent global IT outage, highlighting the risks associated with such deep-level access.

On Windows, any driver that runs within the kernel must be digitally signed by Microsoft. This signature process involves rigorous testing to ensure the driver's safety and reliability. However, the process of obtaining a digital signature can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks. In the fast-paced world of cybersecurity, where threats evolve rapidly, waiting for a new signature with every update isn’t always practical.

To address this challenge, CrowdStrike implemented a unique solution for their Falcon Sensor kernel driver. Instead of modifying the driver itself frequently, they designed it to act as an interpreter for proprietary Channel Files. These files contain specific instructions for the driver, guiding it on what data to collect and when to trigger events.

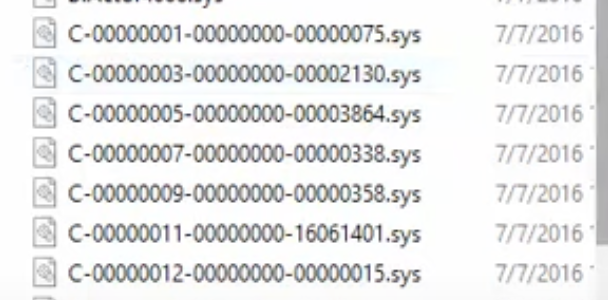

These Channel Files are stored in the %WINDIR%\System32\drivers\Crowd

Strike directory and can be identified by their unique naming convention. Each file starts with a "C-" prefix, followed by a number that uniquely identifies the channel file group, and ends with the .sys extension.

This approach allows CrowdStrike to update and adapt the Falcon Sensor’s behavior without needing to go through the lengthy driver signing process each time, ensuring that the software remains agile and responsive to new threats.

While CrowdStrike’s architecture for the Falcon Sensor driver effectively meets the company’s needs, it introduces potential security risks. The design, which relies on interpreting Channel Files rather than frequent driver updates, creates a gap in the standard security measures enforced by Microsoft for device drivers.

This approach places the full burden of ensuring the driver’s stability and security on CrowdStrike’s Quality Assurance (QA) team. However, it's important to note that this team was reported to have been reduced in size in 2023 as part of cost-cutting measures. With fewer resources dedicated to QA, the potential for undetected issues or vulnerabilities in the driver increases, raising concerns about the overall security of the endpoint protection system.

The Falcon Sensor's architecture required meticulous testing by CrowdStrike to prevent endpoint crashes. However, on July 19, 2024, at 04:09 UTC, the company pushed out Channel File 291. Despite passing initial validation checks, this file contained invalid data that triggered widespread issues.

The deployment of Channel File 291 led to the infamous Blue Screen of Death (BSoD) appearing across various critical systems, including airports, hospitals, and Windows Servers.

Channel File 291 reportedly included instructions related to named pipes, a Windows Inter-Process Communication (IPC) mechanism often exploited by threat actors for Command-and-Control (C2) activities. Due to inadequate validation, this problematic file was distributed to endpoints, causing the Windows Kernel to crash. The driver executed during system boot, resulting in crashes occurring even before user login.